Apparently nothing is sacred at Datsun, not even playing to a capacity crowd for four years with the same successful sports/GT car. Who knows, maybe those long lines of buyers really wouldn’t have lasted forever. Rumor has it you can actually get the color of your choice now. And in some cities, the price has reportedly plummeted to what the sticker says. Not what you’d call a crash in the market, but Datsun is taking those signs seriously. As a result the 1974 Z-car has a new first name: 260. That bigger number means the factory is trying to put more into the car than the U.S. safety and emissions standards are draining out. Be forewarned: It’s an obvious ploy to lengthen the waiting lines again.

The new nameplate stands for a bigger engine: the same basic 240Z single overhead cam six with piston displacement upped by 171 cc (10.4 cubic inches) as a result of a 0.2-inch increase in stroke. Also, the exhaust valves are larger for better breathing, and a magnetic pulse generator has replaced breaker points in the distributor. Datsun engineers claim the new electronic ignition improves starting and forestalls misfiring with the 260Z’s emissions package (lean mixtures, an air pump, and heavy doses of recirculated exhaust gas). And since underhood temperatures have surged in the fight against air pollution, fuel lines are now heavily insulated for protection against vapor lock. The fuel system also benefits from a rear-mounted electric pump operating in tandem with the engine-driven mechanical pump.

.

On the dyno, the new motor delivers 139 horsepower (net) at 5600 rpm, an increase of six hp over last year’s 2394-cc version. Torque is up by 12 pound-feet to 137 (net) at 4400 rpm. Unfortunately, the dynamometer only tells part of the story; the rest is unveiled at the test track. Our test car accelerated through the quarter-mile in 17.8 seconds with a trap speed of 81 mph. As a result of that test, we must sadly report that the big motor Z-car is slower than last year’s edition. The 1973 Z-car we tested went down the quarter-mile in 17.0 seconds at 81 mph. Part of that difference in acceleration can be attributed to extra weight: Our ’74 test car was heavier by 80 pounds with factory air conditioning (optional), with another 80-pound handicap added by the 5-mph front and rear bumpers. But weight in this incidence is not the primary cause of the 260Z’s performance fall off.

Our test car also had a serious drivability problem that put a limp in its gait down the dragstrip. Halfway through the rev range in first gear, the engine simply ran out of fuel. It died like a fish out of water, with power coming back in gulps. Datsun engineers acknowledge the existence of the problem and are diligently searching for a solution. Their tests show that high underhood temperatures are boiling fuel in the carburetors, causing the temporary starvation during sustained flat-out acceleration. The old Hitachi-SU sidedraft carburetors may have come to the end of their rope. We’d suggest electronic fuel injection as a logical replacement.

.

.

.

That won’t happen this year, but still, you should not expect the 260Z to struggle through the model year slower than the 1973 car. Datsun does a sizable amount of development work in this country—oftentimes after the cars go on sale. One whole shipload of early ’73s had to have carburetors replaced on the dock due to a design defect. And later in the model year, a service repair kit was issued to dealers to correct severe hot start problems. The kit included the insulated fuel lines and electric fuel pump now standard equipment for 1974. Unfortunately, the basic problem is still not solved. Emissions hardware has placed such a heavy burden on the engine, that it isn’t ready to make clean air and live up to its power potential at the same time. So at this point, the big motor is less an advantage and more a stop gap measure to meet the law. Any real performance gains over 1973 will depend on how successful the U.S.-based development program is.

The Datsun engineers could stand to take a look at fuel economy as well since that has also slipped for 1974. Our tests show that mileage is down about two mpg from an average of 20 mpg (for a 1973 car) to 18 mpg for the 260Z. Environmental Protection Agency tests, however, have revealed no sacrifice with the bigger engine; in its strictly city driving tests, both ’73 and ’74 models turned in an average of 16 mpg.

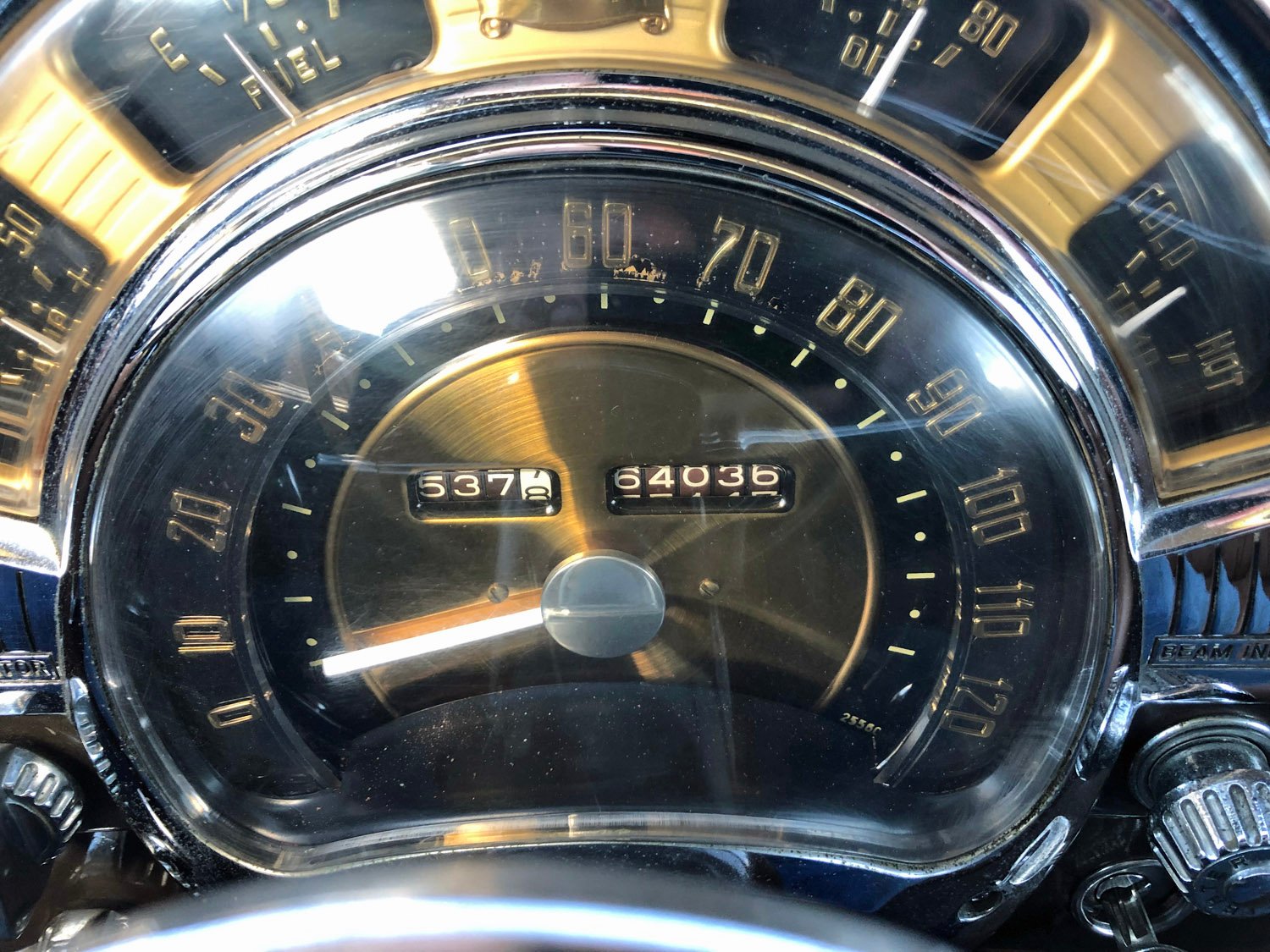

Except for the fuel penalty and one serious flaw in drivability, the new engine is easy to get along with. With the new electronic ignition, it starts eagerly when cold if you use a lot of choke and pulls like a freight train at low speeds. That makes the Z-car more flexible in traffic because you can move out smartly ahead of the flow without resorting to the top half of the rev range. It’s just as well because the tachometer optimistically advertises a thousand revs that aren’t useful. The 260Z is really no different from its predecessor in this respect. The Z-car’s redline has stood at a lofty 7000 rpm from the beginning, and while the engine will wind that tight without bursting, only the noise level is still rising. Power noses downward after 5600 rpm and the useful rev range ends at 6000.

Although the big motor is a mixed blessing, other changes for this year are strict improvements. Datsun has chosen 1974 to unload a fix for virtually every complaint owners have lodged over the years. That’s not to say the 240Z has been riddled with shortcomings. The fact is it has been one of the most popular cars in existence—at any price. Car and Driver readers selected it as the Overall Best Car for 1973, and Datsun is intent on preserving that stellar image.

Handling is at the top of the 1974’s improvement list. In the past, directional stability at highway speeds had been the Datsun’s weak suit: Pre-’74 Z-cars wandered down a windy freeway as if they were piloted by inebriates. The problem centered around a complicated interaction of aerodynamics, steering geometry, and rubber bushings locating the steering rack. For the solution, Datsun has taken no small pains. First of all, the body’s angle of attack into the wind is altered by raising the rear of the car slightly. That diminishes front-end lift at speed and at the same time reduces weight loss from the front tires. With a tighter grip on the road, the front of the car is not so easily swayed from its path by side winds. The steering gear mounting system has also been revised with special attention to eliminate lateral compliance. Side loads that might come from cornering or crosswinds can no longer deflect the steering rack or turn the front wheels. So now only the steering wheel guides the car, as it should. The road feel to the driver is much too damped for our liking, but the 260Z does track down the road with a solid respect for the straight and narrow.

Spring rates are higher at both ends of the car largely to accommodate the extra weight of fortified bumpers and factory air conditioning. Since that weight has favored the front end, there is a built-in tendency toward understeer. But Datsun engineers have wisely side-stepped that bed of quicksand by adding a rear anti-roll bar as standard equipment. It shifts roll stiffness to the rear of the car to counteract the negative handling influence of a heavier front end. On the whole, the new suspension calibration works in a very commendable manner. The 260Z sweeps through turns with a new level of determination: Body roll is at a tight minimum and you can feel both ends of the car working right up to the limit. In the front, there is a gradual loss of response to the steering wheel, but the tires never yield to severe understeer. It’s the rear tires that actually signal the limit as they lose their side grip and begin to audibly scratch at the pavement. You feel the tail slowly creeping out, but the drift angle stabilizes at a perfectly manageable limit because the front end also begins to slide. And it all happens with no feeling of impending doom. In fact, the Datsun is so stable that normal interruptions—more throttle, less throttle, braking, and even wet surfaces—don’t shake its composure. It’s enough to make you bypass the freeway every time in search of a twisty back passage.

No matter what route you take, the Datsun’s interior will deliver you in fine style. None of the strong attributes have been tampered with—excellent instrumentation, wraparound seat backs, and a station wagon’s cargo hold under the hatchback. But most of the shortcomings have been fixed. The hair-trigger gas pedal is gone. And all the rubbery vagueness is out of the shift lever with a new linkage this year. Even the old bamboo-colored steering wheel has been upgraded with padding and a leather cover. It’s not real hand-sewn cow skin, but a manmade facsimile accurate right down to the wrinkles, stitches, and pores, realistic enough to fool a glove manufacturer. Thankfully, the cheap-looking heat-stamped plastic coverings for the transmission and rear suspension towers are gone, replaced by vinyl with a richer texture and a finer pattern.

Factory air conditioning is also a major upgrade this year. The hardware is a marvel of technology—lightweight aluminum materials for the evaporator and condenser, and a compact swashplate compressor similar to the GM/Frigidaire design. The compressor is vibration free in operation, and there is no underhood clutter with the new system. Inside the car, the hardware is shrewdly interfaced with the instrument panel. The heater/AC control module is one of the simplest and most informative layouts we’ve seen. Three carefully marked levers regulate the interior climate: one four-speed blower switch, one temperature selector, and one function knob. Since the latter is graphically coded with red and blue arrows, you know if the air has been heated or cooled and exactly where it’s going. At last cryptic labels like “Bi-Level” take on a solid meaning.

The air conditioning system is the only convenience Datsun doesn’t include with the base price. For $5125, you get tinted glass, intermittent wipers (new this year), a dead pedal for your left foot, and even an AM/FM radio complete with an electric antenna.

True, it’s not the bargain it was in 1970 at $3526, but a serious competitor to the Z-car still hasn’t materialized. The opposition is slimmer by two cars this year with the demise of the Opel GT and Triumph’s GT6. The remaining field, the Alfa GTV, the Jensen-Healey, and the Porsche 914, may delight purists, but the technical fascination doesn’t seem to sway the masses shopping for a sports car at Datsun. Face value is the key: The 260Z offers a bigger engine at a lower price. Not to mention the comfort of joining a crowd—a mass stronger by 54,000 happy customers in 1973.

We don’t expect a downturn in popularity even with the drivability problems wrought by emission controls. The upgrade program has been too thorough for that to happen. And if the carburetor engineers can get their act together, they’ll wipe out the 260Z’s most menacing competitor—last year’s 240Z.